The FMLM Trainee Steering Group have worked alongside various supporters to develop a range of 'How To' guides to help trainees successfully complete projects.

We encourage you to make the most of these resources and share with the TSG any suggested topics for future articles.

- How to get involved with leadership and management as a student and foundation doctor

by Dr Christina Whitehead

Image

Engaging with leadership and management may feel like a daunting task as a student or junior member of staff. If you follow just a few of these 10 simple tips you will make an effective start, and be able to evidence that you are engaging with an essential part of your curriculum.

1) Lead a QI or audit project

An important thing to realise as a junior doctor is that you have a leadership role every day on the wards. Many of us now also have community rotations which is a great setting to run an audit or quality improvement project and prove that it is possible to lead the way in improving patient care. Similarly, the vast array of extra-curricular activities available for medical students provide similar opportunities to hone leadership and management skills.

2) Attend a conference

A great way to show your commitment to leadership is to attend a relevant course or conference, such as the FMLM and BMJ’s Leaders in Healthcare annual event.

3) Student/junior doctor membership of a society

Many societies offer discounted rates for student membership or junior doctor management. Joining and engaging with these societies, such as the FMLM Trainee Steering Group, will give you information and opportunities to access and build your skills.

4) Join the doctors mess committee / medical society

Having a formal role on a MedSoc or your local junior doctors committee should not be overlooked. Organising events such as socials or formal events can prove that you have the organisation and leadership abilities that are essential transferrable skills.

5) Become a regional representative

Many societies, (such as the FMLM’s Trainee Steering Group, ASiT, or BUSOG to name a few) have a representative for each region of the UK. Keeping your eye out for opportunities on a society relevant to your interests is always a good idea.

6) Organise an event for your colleagues

Whether this be a teaching session, a careers day, a workshop or a conference, having the initiation to plan a local or national event shows dedication and is a sign of developed leadership and management skills. Be sure to gain some feedback too that you can keep and reflect upon.

7) Apply for the National Medical Director’s Clinical Fellow Scheme

An opportunity to spend 12 months out of programme aimed to fast track doctors who have potential to develop as medical leaders. This can be done any time after FY2 – so always worth considering between your foundation years and specialty training, as well as later on. More information can be found on the FMLM website.

8) Set up your own society

Setting up a society in medical school, no matter how small, is a way of developing your leadership and management skills. Going through that process will be a valuable way of gaining confidence as a leader and experience in managing others.

9) Contact your hospital’s chief executive / medical director / medical student dean

Many hospital or medical school meetings may benefit from the voice of a medical student or junior doctor sitting in the room. Many of the leaders want to hear our views, and acting as a spokesperson will build experience and confidence.

10) Engage on social media

The role of social media is becoming increasingly important when acting as a leader. Engage with your local hospitals, your medical schools and relevant societies such as the FMLM or TSG to stay up to date and be the first to hear about local and national opportunities. We can be found on Twitter using the handle @FMLM_TSG.

- How to be a junior doctor on social media

By Dr Kaanthan Jawahar

Social media use as a professional can be daunting. Doctors often worry that what they post will land them in trouble with a host of people, such as their employer, regulator or the patients they look after. The reality is though that, with due consideration, such occurrences are rare and the overall benefits of social media use for doctors clearly outweigh the risks.

Regulation

The main piece of guidance to be aware of is the GMC’s Doctors’ use of social media (2013) [1]. Though dated when we consider how fast social media has progressed in recent times, the premise it is based on is that of Good Medical Practice [2]. The main points to take away are:

- If you plan on maintaining a professional medical presence on social media, you should use your real name as it appears on the GMC’s medical register.

- If you have separate personal and professional presences on social media, but you are contacted for medical advice through a personal account, the GMC state that you must redirect that query to your professional account.

- The GMC’s guidance on behaviours as a doctor also apply to social media; this includes bullying, harassment, making unsubstantiated comments about individuals/organisations etc.

- Being aware of privacy; even when forums are closed there is a possibility that comments can be traced back or a screen shot taken. Furthermore once something is posted online it can be difficult, if not impossible, to fully remove from the internet.

It is also usually the case that your employer will have an internal policy on social media usage of their employees. Usually these are about avoiding bringing the organisation into disrepute, with considerable overlap to that which the GMC have already set out.

The Benefits

Social media has changed the way information is disseminated. It is often the case now that news is first communicated through this medium. The growing number of users across various platforms also allow for discussions to take place between professionals, such as doctors, and other stakeholders, such as patients, commissioners, academics etc. In the health policy world, you will struggle to find a report launch that is not accompanied by a robust social media dissemination strategy. Social media platforms (especially true with Twitter) make senior figures more ‘reachable’ with their responses heavily scrutinised by the wider social media community, arguably improving transparency.

On a personal professional level, social media offers a doctor a way to communicate with patients from their specialism, academics driving clinical advancement, policy makers that define service delivery and colleagues within healthcare. Previously the only real way to achieve such a reach was through large and often expensive residential conferences, however even those events are now heavily reliant on social media.

So how do you make the best out of a social media platform, such as Twitter?

Personal professional social media presence

If we use Twitter as an example, the first thing to do is join. Yes there are all sorts of worries and stories about things going very wrong, but if the advice in this guide is followed it is unlikely that such horror stories will happen.

- Comply with the GMC’s social media guidance – You should identify yourself with your full name on your profile and say that you are a doctor. It is up to you what else you place on your profile (e.g. specialty, professional affiliations, employer etc.). It is important to be aware of any other ‘local’ policies on social media. These include, but are not limited to those from your employer and any organisations where you have identified an affiliation. You will often see Twitter users write ‘views my own, retweet does not equal endorsement’ or words to that effect. There is nothing wrong in stating this, but be mindful that the very fact that you are a medical doctor can mean that lay people hold your opinion in a high regard – and similarly are quick to scrutinise what you write.

- Identify who you would like to follow – You will have joined social media for your own professional reasons. Use these reasons to guide what you wish to engage with. An example would be that your interest is in health policy, therefore you would follow organisations like NHS arms-length bodies, think tanks, professional associations and their employees/representatives. This makes your Twitter feed ‘relevant’ to your interests.

- Identify how you wish to engage – It may be that you wish to use Twitter as a type of read-only ‘news feed’. That is perfectly acceptable. You may feel that you wish to get into conversations online, ‘replying’ to tweets from those you follow as well as ‘liking’ and ‘retweeting’ (disseminates to the twitter feeds of those that follow you) certain tweets. It may be that you want to send out tweets yourself to your followers, who may then reply to you and/or retweet your tweet to their followers. You can also be contacted by direct message – whilst this does not appear on public Twitter feeds, be mindful that this information can be easily ‘screen-shotted’ and disseminated.

- Be aware of ‘trolls’ – There will be some on social media that fundamentally disagree with your views. Often this is where the most enlightening conversations happen. However there are some who are unlikely to engage in productive debate, and may look to marginalise you or even target you with abuse. It is best to disengage with such individuals on social media as you are unlikely to ‘win them over’; attempting to do so may cause you more harm than good. Social media platforms usually have ‘mute’ options or the ability to block someone. Where clear abuse is taking place there are procedures to report that person to the social media platform you are using.

Suggested Twitter etiquette

It can be very easy in the heat of the moment to tweet something you later regret. There is no one way to guard against this and people often have and develop different approaches to using Twitter. As medical professionals we do possess transferable skills that can help with this (technical expertise, critical appraisal skills, written communication etc.) and it would be remiss of us not to use them.

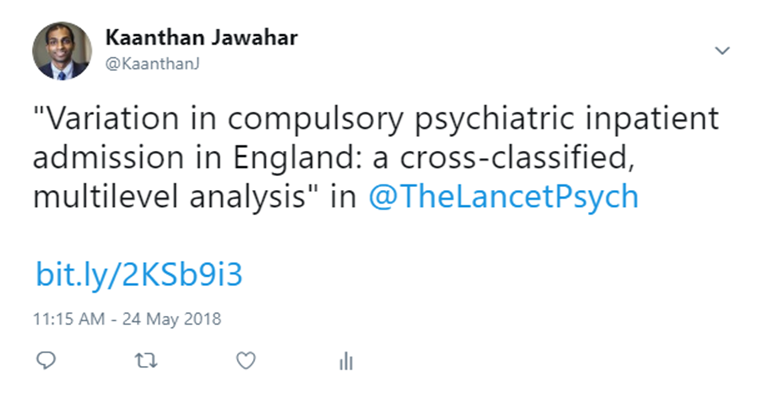

To illustrate I have provided an example below of how this can be achieved, using the publication of a peer-reviewed article from my specialty (psychiatry) from 2017. The aim of this is to present facts with a personal interpretation and a link to current policy work to emphasise relevance. This is something any medical professional could do within their own field of expertise.

Image

Using my personal account I have composed a tweet that consists of the journal article’s title and the Twitter handle of the journal it is published in. The aim of doing this is so the journal is aware that I have sent out this tweet – this will allow them to ‘like’ and/or ‘retweet’, which would extend the reach of my tweet. I have also provided a link to the article, and used a URL shortening website for aesthetics (here I used bit.ly).

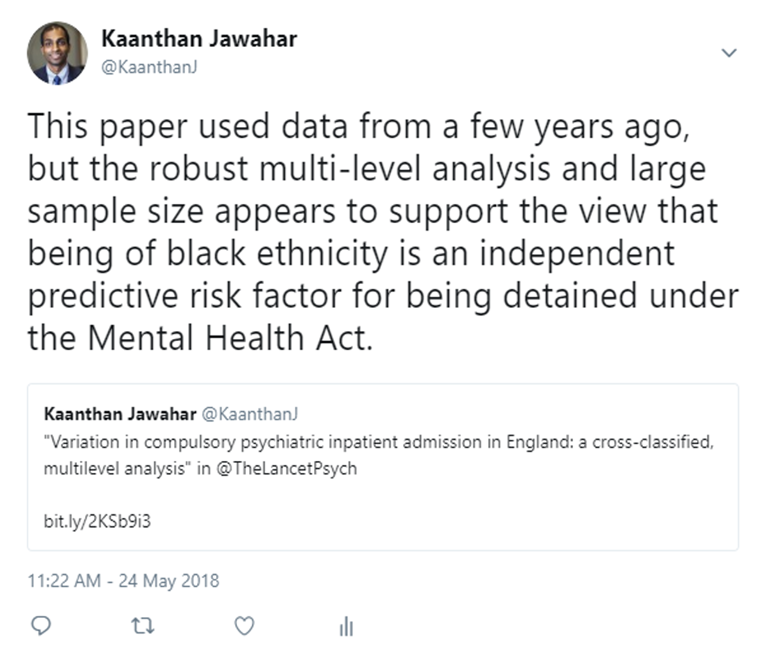

What I have done here is offer a summary of the author’s conclusions. In addition, I have ‘quoted’ my initial tweet, so that the link to the article is still easily available. Quoting your tweet is done through the ‘retweet’ button, but you would ‘retweet with a comment’.

Image

Finally I have replied to my second tweet linking this journal article to current policy work. I’ve used the Twitter handle of the person leading this independent review, again in an effort to increase exposure. I’ve also provided a direct link to the interim report of this group that corroborates this. To note: replying to your own tweet creates a ‘thread’. More can be added to the thread by clicking the ‘add another tweet’ option.

Summary

To reiterate what was mentioned earlier, everyone has differing styles on social media for professional use. The 5 key points to follow are:

- Don’t be afraid of social media. With a few tools and understanding of appropriate professional use, the benefits far outweigh the risks.

- As a medical professional, utilise the skills you already possess; communication, critical appraisal, debating etc.

- The GMC’s social media guidance and Good Medical Practice outline certain 'shoulds' and ‘musts’ if you are to identify yourself as a doctor on social media.

- Each social media platform has different ways of use – identify what you wish to get out from said platform and tailor accordingly.

- Enjoy using it! Social media has revolutionised communications on a global scale. In the same way that medicine progresses on a daily basis, it would be remiss of us to not keep up with the times.

@KaanthanJ @FMLM_TSG, FMLM TSG External Communications Lead

References

- Doctors’ use of Social Media. GMC. 2013. Accessed 14/05/18 https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/doctors-use-of-social-media_pdf-58833100.pdf

- Good Medical Practice. GMC. 2014. Accessed 14/05/18 https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/good-medical-practice---english-1215_pdf-51527435.pdf

- How to manage your peers

By Dr Iain Wallace

The challenge of managing your peers

As a medical leader one of the biggest challenges you can face is managing your peers. Essentially that means getting them to buy in to your vision or ideas and to change their behaviour accordingly. As a doctor the things you want your colleagues to do varies enormously from turning up on time for a shift through to improving your organisation’s standardised mortality ratio. Both require good leadership skills but need to be deployed differently depending on the context. If you want a colleague to change their behaviour it helps if you have an established relationship with them. So, building trust and rapport with colleagues is important even when you might not feel an immediate need to ask them to change or do something they might not otherwise be inclined to do. That can be achieved in many ways but being approachable and interested in them as a person goes a long way. Also being willing to help out (even better without being asked) is another way of building good working relationships. That by itself is no guarantee that you will get an easy ride but it’s definitely a prerequisite for being able to successfully manage colleagues. Being fair is a trait that also helps. It is not good if colleagues perceive you as having biases and are only interested in promoting things dear to you. Good self-awareness through being open to colleague feedback can help counter unhelpful tendencies!

Communicating with your team

If you want to be effective as a doctor leading a team it is important that you have defined goals and can communicate them clearly and with some confidence and enthusiasm (but not so much it’s a turn off). However, in formulating your goals it’s important that you share your thinking and incorporate others’ ideas as appropriate. That way you don’t spring surprises on people and those whom you want to embrace your ideas etc will hopefully be half way there already in their own minds which makes your job all the easier. Having said that, don’t expect things to always go smoothly. They don’t, that much is guaranteed, and that is where personal resilience is also important (see another quick guide). One way of getting people on board early is to arrange a meeting of colleagues to discuss your thoughts. This allows you to sense check them and invariably, as more minds are usually better than one, you get some helpful feedback that allows you to refine your idea. For busy colleagues writing a short SBAR and circulating it ahead of the meeting can be helpful.

In some peer to peer situations you may have the luxury of position power, for example if you are a Chief Registrar or Chief Resident. However, it is important to see the use of position power as a last resort as the more you use it the weaker is its effect. You certainly don’t want to deploy it in situations where with a bit of effort you can achieve the result you are looking for.

Being persistent to achieve success

If things don’t go accordingly to plan don’t be discouraged. It takes determination and persistence to get things moving at times. Remember inertia is almost the natural state of things! Sometimes the reason colleagues don’t respond enthusiastically to your ideas is simply down to time pressures. That’s when persistence is helpful. However, if non-one is buying in to your grand plan then you need to spend some time with them understanding why that is rather than keep flogging the proverbial dead horse. Of course, if you engage people early there is less likelihood of that happening but there are also late adopters in most workplaces who resist change. In some cases you can just work with the enthusiasts and eventually the others come on board but on other occasions the resistors can win through attrition, so identifying who they are likely to be ahead of time and working with them to build support is a wise move. This still isn’t a guarantee of success, of course. If things don’t work out don’t get down about it as it’s normal! Have confidence in yourself but use this opportunity to reflect on why things didn’t work out and apply that learning when there is another opportunity to work with your peers on another idea that you have.

- How to run a successful conference

Running a conference is something you may need to do as part of a society or group or as part of your involvement in a particular interest group. Conferences can be fun and create a great opportunity to meet some interesting speakers. It is a good way of bringing people together be that within a speciality, society or just an interested group. Conferences are a fantastic way of sharing learning to a wide number of people and creating opportunities for trainees to showcase their work in oral and poster presentations.

From a personal perspective organising conferences:

- Give an opportunity to meet and listen to speakers of particular interest

- Demonstrate your leadership and organisational abilities

- Meet like-minded people and share ideas

- Extend your professional networks

- Develop skills in reviewing abstracts and shortlisting

A word of caution, despite being lots of fun, organising a conference is hard work and can leave you tearing your hair out at times. I have run a number conferences and have learnt a fair few lessons which I have incorporated into this ‘how to guide’. It will provide you with a structure (the steps) when you are starting out and hopefully also a few handy hints and tips.

Tip – Before you take on organising a conference – remember this will take time – this not something you can pull together in an afternoon. It is difficult to say how much time this will take, but you need to be motivated and proactive. Get a good team around you - why do it alone?

Step 1 - The proof is in the plan

Job number one is planning. You need a clear idea of what is it you want to achieve with a conference.

The following questions can be useful to start framing what you want to do.

- Who is the conference for?

- How many people do you hope or need to attend?

- Do you have the funding or do you need to raise funds?

- Will there be a cost for attending the conference for delegates?

- Are you planning to provide refreshments?

- What is the theme/ topic of the day?

- Do you want workshops/ keynote speakers or a mix?

Step 2 - Getting off the ground

Once you have laid your plans there will be a few things that need to be sorted as a priority:

- Setting a date – depending on your target audience, remember to think about when school holidays, key exams and interview times are as this may detract from attendance.

- Finding a venue – There are often loads of great places around depending on your budget. You need to think about transport links – will people drive or come by public transport?

- High budget – Hotels/ stadiums are usually a good start. They have events teams and will sort all of the catering, refreshments and stationery.

- Low budget – Education centre’s at Trusts are usually good and usually free. You may have to sort your own catering.

Tip - If you don’t have a budget – consider getting drug reps/GMC/MDU/MPS to sponsor an event. Each area will have a local rep – look on the website for their email and contact them or approach a rep that you may have seen at your place of work. They may not be able to provide funding, but they may be able to provide lunch in return for delivering a short talk.

Tip – Think very far in advance (around 3-6 months) – people are busy, and time vanishes.

If you have your heart set on a particular keynote speaker, email them early with a range of dates, your venue may be more flexible than the speaker's diary!! Also, set a deadline for a response and, as painful as it might be, if you don’t hear back move on. Don’t delay if they don’t respond. In my experience, most speakers are more than happy to come and speak when you explain you are a junior doctor organising a conference for other junior doctors. You could offer to pay for expenses but not offer a fee!

Step 3 - Pulling together the agenda

OK, so you have your venue, the date and hopefully some speakers, now is the time to start thinking about the rest of the agenda.

- Do you have workshops?

- Do you need additional rooms for breakout sessions?

- Do you want trainee presentations/posters? (Remember this may be a pull for people to attend the event and an excellent opportunity for people to showcase their work)

- What are the timings? Factoring in time for coffee and movement between sessions is important.

Tip - when asking for Trainee presentations - create a marking template beforehand and rope a few people into marking them, this can be more time consuming than you think.

Tip - Give the speakers a clear brief or additionally a call before the event - There is nothing worse than a speaker that has got the brief wrong.

Ask speakers for slides in advance if possible so you can a) you can check the message is what you want and b) you can load it up on the IT system before their arrival.

Step 4. On the day

Before the day – allocate roles and responsibilities. Some suggestions of these could be:

- Reception and sign in

- Meeting the speakers

- Introducing speakers and workshops

- Liaising with the venue – find one person to talk to the events person (you can go to them with any queries or event type concerns)

- Marking posters

Most of all – try to enjoy it yourself and make sure you get to attend sessions and participate too.

Step 5 – The final hurdle

Congratulations, the conference has been a success…however, before you sit back and chill there are a few things to do after:

- Thank speakers

- Certificates for delegates (one trick I’ve used is to send then and only release certificates of attendance on completion of feedback surveys)

- Review feedback and share with appropriate parties.

Step 6 – Sit back, RELAX and pat yourself on the back for a job well done!

- How to engage patients and the public: lessons I have learned

Prof Keith Willett, Director for Acute Care, NHS England,

Image

When we have opportunities for service changes, are planning redesign of clinical space or developing clinical research it is absolutely essential to have the perspective and input of members of the public and patients. Of equal important is their help in crafting the best ways to explain things to other patients or users. But we often fail to do this, engage too late and in my experience it can often be tokenistic to tick the ‘PPI’ (public and patient involvement) box.

So as a clinician involved in service redesign all my career, in serious clinical research in the last decade and in recent years managing some of the most difficult patient safety and controversial policy issues I have been asked to share solutions that I have found successful and valued by our PPI representatives.

Starting out

Perhaps the first step is to decide what sort of help and advice you need; there are several options. These range from the ‘public’ general member of the community, but even then what ages, gender, carer characteristics best fit your need. So called ‘service user’ (an appalling term, I prefer people) can be patients who are ‘experts by experience’ because they have the condition or use the service you are looking at; they can be general patients from your own practice or ‘professional’ patients from one of the national patient organisations who are well versed in the illness, how health and care services work and familiar with contributing to panels or groups.

Having said all that despite the one million people who use the NHS each day we often fail to secure or retain the sort of PPI advice we need. So how do I do it now after years of trial and error. In my view you reap the greatest benefit by really valuing the contribution of those who agree to help and overtly seeking their contribution. Remember it’s quite daunting for members of the public to join committees or groups full of professions on several counts. It is an audience they often greatly respect and may be grateful to for treatment. They will usually be heavily out-numbered by real experts as they see it and whether it is matters relating to clinical care, new treatments or building design the language and terminology if often complex, jargonistic and technical. It not surprising they turn up, understand little, and contribute less or nothing and you as chair feel as embarrassed as them.

So what’s my practice now?

Firstly take time to ‘spot’ patients in your clinical practice who might be willing and appropriate, but beware you don’t just end up with early retirees! Students, mum’s with children of school age, those out of employment are valuable, diverse in culture and surprisingly willing. Just ask if they would be open to an approach sometime in the future and if they are open to that add them to a list you keep.

Then when you have a project, if they still are willing, ask if you (or one of your team) can send them some simple information and follow that up with a call. Take time to interview them so they know what they committing to and you have an idea of what you will get. But for me the real lesson is how you handle meetings. Firstly allocate them a ‘mentor’ from the group they are joining – someone who can arrange a pre-call with them a few days before each meeting to walk them through the papers, explain the context, clarify the intent and demystify the language – help them frame any questions or thoughts they would like to convey. Then in the meeting, and for me this is the real golden nugget (found by accident!), the first main agenda item is to ask each PPI rep to give their reflections on what they took from the last meeting, and what if any general thoughts or ideas they would like considered by the group from their reading of the current meeting papers. Giving the PPI representatives primacy in this was has in my experience a profound effect on the meeting. The expert members immediately change their language and avoid, offer an explanation for, or apologise for technical speak. Often one expert will interject an explanation as they keep one eye on the PPI reps. Indeed I often find the experts stop addressing the chair preferring to seek non-verbal reassurance from the lay members that they are adequately explaining their point. The compounding advantage is the growing confidence and contributions of public and patients members. Then shortly after the meeting and of equal importance, and valued by the lay reps, is the role of the mentor in speaking with them to explain anything that was not understood and in so doing start to prepare their contribution to the next meeting.

What is success?

Well it must be seeing the PPI reps influence and literal ‘fingerprints’ all over what you have produced as a committee; it’s also experts who have really valued the patient involvement and usually a sadness at the closure of relationship formed in the committee – or perhaps it’s that you will not struggle to find someone to help out next time.

- How to run a successful recruitment campaign

-

By Dr Robin Som

I have been a member of the FMLM Trainee Steering Group (TSG) since its inception in 2012, in the role of recruitment and engagement lead, and the past year has been a challenging, fascinating, and rewarding one for me.

The dynamic nature of medical training means many trainees come and go from the TSG. Last summer, due to exams, role changes and other reasons a number of the regional representatives stepped down, or were in the process of stepping down. Recruiting to these roles was a priority, as was due consideration for FMLM’s aim to ensure representation of all four nations of the UK. So, we initiated a recruitment drive that ultimately appointed new representatives to all eight regions in the UK.

How did it work? The first step was to establish terms of reference for the roles; the TORs, as they’re called, inform any new members of their roles and responsibilities, and form the basis of the person specification. This was especially crucial at this point in time as in the past we had noticed that vague and non-binding TORs had, to some extent, been one of the contributing factors to the high turnover of team members. The TORs were created with input from all existing members of the TSG, which, I hope, will help give the group structure and shape in forthcoming years.

Publicising the roles was the next step. We used our Project Bank (now replaced with a Jobs and opportunities page) and social media to advertise all vacancies. Drawing attention to the roles was certainly one of the biggest challenges. We received several applications from some regions, but none from others. It was difficult to pinpoint why this was. To overcome this we implemented a focused strategy for each region. Through FMLM, we contacted trainees in regions where representation was needed. Judith Tweedie, FMLM’s clinical fellow at the time, and I got in touch with all senior leads and asked them to explore their own network for potential candidates. This proved to be the difference, after which we received multiple applications from most regions.

Interviews were conducted by conference call and revealed a range of personalities, experiences and skill sets. We spoke to doctors who had just graduated, doctors who were two years from CCT, and many in between. Some were in the middle of research or out of programme stints, while others were full time clinicians. However, there was one common quality I noted in all candidates, and that was the passion for leadership and change. This made appointing just one representative to each region very difficult – were it up to me, we would have appointed entire committees per region! Although, it was heart-warming to know that talented and committed doctors are out there, keen to contribute in these difficult times.

I feel very lucky to have coordinated this recruitment drive, the biggest in the TSG’s history. It has given me the opportunity to work alongside some of the most experienced and senior doctors in medical leadership and management, and this is one of the aspects, where I feel I have gained the most. Both in this TSG role, and in my daily role as a surgeon, I sometimes struggle to communicate effectively with those more senior than me. Consultants can be intimidating, but this experience has helped me realise the kindness, patience and flexibility of individuals. If you show initiative, step forward and seek it out.

It has been a privilege to talk to trainees across the entire country and hear their thoughts on the state and future of our NHS. It was a wrench to turn away promising candidates, but the door is always open to anyone who would like to engage with the TSG in the future.

One surprising lesson learnt was the triumph of the personal touch over social media. I have long been an advocate of social media to reach large audiences, and the rest of the TSG team and the FMLM office can confirm. It transpired that that personal emails and using the networks of the senior regional leads was what led to the upturn in applications. In an era where a 10-character soundbite or one photo can be broadcast to millions in a second, it was good to see that personal conversations can engage and draw attention to a cause - having said that, perhaps what I really need is a tutorial in tweeting!

- How to chair a meeting

-

By Dr Judith Tweedie

My first go at chairing a meeting was what would be best described as a disaster. I didn’t really understand the role of action points, agendas or minutes or how you made them happen in reality. Worst of all the meeting ran forty-five minutes late. With some gentle begging and maximising the tug of professional responsibility, the participants did agree to return for a further meeting. It was apparent I had a lot to learn. I volunteered to chair more meetings, watched and heard from the experts and, like every good professional did a google search into what makes a great chair. These are the lessons I have learned which I hope will be of use to anyone presiding over a meeting.

Firstly, chairing a meeting is challenging and something few get much training in. Effective chairing is critical to successful meeting and requires preparation and awareness of the roles and responsibilities.

Preparation for chairing a meeting

The most important question to ask first is, do we need the meeting? Could email or a face to face meeting with the main players be a more appropriate and more convenient form of communication?

Be clear as to the overall aim and prioritise the objectives which will have the most impact in reaching this aim. Ensure the agenda is clear, concise and will achieve each of your objectives and move you towards your overall goal.

Who do you need in the room achieve the aim? Participation can evolve, you can nearly always add contributors as the work proceeds, and you recognise gaps in expertise.

What format will the meeting take? In person, via teleconference or a mixture of both?

How long will you need for the meeting, remembering that time is precious to everyone involved including you? How long will these meetings continue for: six weeks; six months; five years?

These questions are worth reviewing after every meeting.

The details

Every meeting should have a dedicated person to take ‘minutes’ (a written record of what is said in the meeting) and record the action points (see later). Minute taking is quite a skill and it useful to identify beforehand who will undertake this role. There may be dedicated administrative assistance, if not, it can be helpful to make a rolling rota for the minutes and agenda (described next) which includes all the participants in turn.

The agenda lays out what is going to happen in the meeting and is crucial in keeping the meeting focused and productive but, more importantly, it is also the chairs secret weapon in keeping overly enthusiastic participants on track. The agenda items are the topics that need to be discussed to achieve the overall aim. Keep longer items towards the start of the meeting when attention is at its best. For difficult or sensitive topics, you may wish to table these early in the session, to get it over and done with, or mid-meeting when everyone has warmed up somewhat. Avoid leaving difficult topics to the end as there may not be enough time to resolve issues which may result in the meeting finishing on a negative note.

The roles and responsibilities of the chair in the meeting

The chair sets the direction of the meeting, facilitates fair and proportionate member involvement, listens and draws together the most important points before setting clear, actionable plans. It is often better that the chair is not actively involved in the delivery of most the actions as it’s hard to maintain oversight if too engaged in the detail.

To begin with, you may wish to go over some basic information such as fire drills, locations of toilets and whether mobile phones are required to remain on silent. Some chairs choose to reinforce ‘rules of engagement’ such as respecting others opinions, avoiding talking over one another and focusing on genuine questions. This is the prerogative of the chair and how you feel most comfortable working.

Action points

Start by outlining the purpose of the meeting and what you hope as a group to achieve. Run through the action points which are the tasks or jobs participants agreed to undertake at the last meeting. For example, the finance person may have been identified as the best person to solicit tenders for equipping an outpatient clinic. The action point would then be ‘Mr x to seek tenders from external companies by the next quarterly meeting’. At the next session, the chair then checks Mr X has completed the task. It should be clear who is responsible for the delivery of each action point, and this should be recorded within the minutes.

Action points are crucial to ensuring progress between meetings, and it is the chair’s responsibility to ensure these are clear, actionable and equitable. If you don’t have any action points, then you need to ask yourself again do you really need these meetings?

The bulk of the meeting

The content of the meeting and the structure will depend upon the stated objectives of the project which form the agenda items.

The chair’s key responsibilities during the meeting are to keep the meeting focused and on time, ensure all participants are included in the meeting, maintain an overview and summarise key decisions and action points (see five top tips). A well-structured agenda with allocated time sessions can help with this.

At the end of the meeting, the chairperson should sum up, remind the committee members what they have accomplished and thank them for their attendance. If possible, the date and time of the next meeting should be identified or reiterated.

Five top tips

1) Preparation is vital

Know why you holding the meeting and what you hope to achieve from it. Where possible circulate agendas and pertinent background information in advance.

2) Keeping to time is a make or break

If you want committee members to return for the next meeting, keep to time. Start and finish on time and where possible build some leeway in the agenda for overrun. Think about timing items on the agenda; this gives members clear guidance about the time allocated to their discussion point.

3) Don’t avoid the difficult conversations

This can be particularly challenging. Watch for cues and body language which signals that individuals are not happy and try to address this, sometimes directly. Giving members the opportunity to air grievances will often feel awkward and unpleasant, however, when handled respectfully and professionally by the group, will ultimately build trust, improve teamwork and improve outcomes.

4) Make sure everyone has their moment in the sun

Everyone wants to feel that they have been listened to and their opinions or concerns heard. Bring the quieter people in tactfully. Balance this carefully with maintaining oversight and not allowing one or two people to dominate the meeting (including yourself!)

5) Accept that you won’t always get it right

Chairing is challenging and well done for stepping up to the plate. No-one can get it right all the time and certainly not in the beginning, keep actively seek feedback (and yes it can sting a bit) and remain open to areas of improvement. That is what will make you a great chair..

A leader's dynamic does not come from special powers. It comes from a strong belief in a purpose and a willingness to express that conviction.

- Kouzes & Posner

Thank you to the RCP London Chief Registrars for reviews and comments.

- How to run a successful workshop

-

By Dr Judith Tweedie, FMLM Trainee Steering Group Chair and Mr Stephen Harding, Specialty Recritment Office, Royal College of Physicians

What do we mean by ‘workshop’?

The term workshop can be used as a broad church to describe ways of meeting that break out from the traditional board room style meeting. Perhaps describing a workshop can be better done by contrasting it to the expectations of a normal meeting:

Meetings:

- Commonly used to facilitate an exchange of information and confirm agreements/decisions

- Often have a wide ranging agenda covering disparate topics

- Structured by all participants discussing together for the duration – usually sitting round a table

- Led by a chair who manages the discussion and confirms the outcomes

Whereas workshops:

- Better method for creating ideas, building or refining processes or problem-solving

- Designed to produce a particular output or series of outputs, focussing on a single issue, or one issue at a time

- Use a variety structures to achieve aims, likely to involve breaking out into groups

- Facilitated by a lead who administrates the session but does not participate in activities

Although workshops tend to have a defined output, there is no limit to what this could be, examples include: delivering training, engaging stakeholders, brainstorming or refining processes.

What are the key elements to a successful workshop?

Well-defined goal (or goals)

The aim and objectives should be clear and communicated to participants. Without a clear goal, you should not hold the workshop.

Planning

As with most things in life, success does not happen by accident. Workshops can appear to be chaotic as they often involve participants moving around and can be quite noisy. Therefore it is all the more the important that you have considered everything in advance so you know exactly how you expect it to run and build contingency or flexibility into your timetable. A crucial element is matching the objective with a method which will achieve that in the best way possible and to consider how to make the workshop interactive and interesting for participants.

The facilitator

A well designed plan goes a long way but it takes a well prepared and strong facilitator to maximise the chances of a successful outcome. Facilitators need to be disciplined to stay on track, familiar with the plan and able to control the crowd. It can also be helpful to be good at thinking on your feet, flexible and imaginative if things start to get off track.

Lively/fun

Providing an environment which participants will find interesting and fun will improve the engagement and output of attendees. Workshops are a real opportunity to be imaginative and to break out from the highly structure environment usually seen in meetings. Create activities which will allow all participants opportunity to get involved as much as possible.

Engaged and relevant attendees

It is vital that you involve the right people and those people are engaged participants. You can do your bit by achieving the elements above but also making sure that the right people are in the room. Factors to consider include: who are the experts or people affected, getting a range of different stakeholders, ensuring key people attend, getting buy-in from management.

Successful engagement is the building block to a successful result. Whether the objective is to improve a pathway or create a national consensus document engaging the right people at the right time in the right way is fundamental to meaningful spread, adoption and implementation. Workshops can be a particularly effective method of engaging with the people who will be essential to the project’s success.

The pros and cons of workshops

Pros

- Efficiency - allows engagement with several relevant parties in one sitting

- Idea generation - properly facilitated workshops can produce a large range of ideas with participants bounce off one another, create new ideas from the synergy of different perspectives.

- Maximise attendee input – meetings can be daunting for many attendees so workshops can offer a safer environment to speak up for those less confident but whose ideas are likely to be equally relevant.

- Team building – relationships can be built as participants can work with others from diverse backgrounds within the field, offering an opportunity to network and cross pollinate.

- Shared ownership – as workshops aim to utilise attendees to solve problems, a sense of ownership over outputs can be created. This differs from meetings which can become adversarial by taking it in turns to get across your view in the strongest way possible to affect the decision.

- Workshops also have potential to create an engaged group which can function as an excellent sounding board as the project proceeds.

Cons

- With a broad range of stakeholders in the room, there is always the potential to go off topic and not meet the stated objectives.

- Can bring extra costs to the project such as room hire, travel expenses and sustenance. Workshops also require a significant time commitment from participants and organisers.

Who should attend?

Attendees will be entirely dependent on the aims and objects of the project and what are the desired outputs of the workshop.

For example, a workshop may be a useful tool during implementation of a new admissions pathway for medical patients over 75 years of age. Workshops can be used to either generate or test processes behind the pathway. In this example, the workshop lead may invite medical, nursing and allied health professionals from geriatrics, A&E, general medicine and general practice, general managers, administration staff, bed managers and patients. Each is likely to bring a unique perspective to the project and prevent necessary steps being missed.

How do I structure it?

There is no one way to structure your workshop, the key is to start by considering what you wish to achieve and work backwards.

The Surprising Power of Liberating Structures by Henri Lipmanowicz and Keith McCandless details a variety of techniques for how you could manage your workshop to get you started but use this as a starting point and do not feel you have to be constrained by following techniques to the letter.

Here are some general tips about structuring to get you thinking:

Group work

Splitting participants into groups is a classic workshop trick but the reason why is that it works and it gives more participants the chance to contribute at any one time. There are things you can do to make the most of using groups though:

- The ‘1-2-4-ALL’ method detailed in The Surprising Power of Liberating Structures, is a way to build up towards larger groups, giving everyone the chance to have their say in a short time.

- Think about how you split groups up to split up cliques or spread types of stakeholders. One way to randomise it is to allow people to sit where they want and then start assigning numbers for as many groups as you want. You then ask each number to gather together; this automatically splits up those sitting at the same table.

- When gathering feedback from groups, get one point at a time from each group to avoid the first one grabbing all the glory.

- Avoid repetition and save time by asking participants not to repeat points made by other groups.

- If you are covering multiple topics, split groups up to create more networking opportunities and exposure to different ideas.

Ranking

Many people like putting things in rank order and doctors more than most. Using methods to allow participants to rate options is a sure way to get attention. One way is ‘25/10 crowd sourcing’ or ‘dot voting’

Storyboarding – this is stolen from Liberating structures so better reference it

Can you structure your workshop so that individual elements support each other. For example:

- an icebreaker to get everyone talking to each other

- 1-2-4-ALL to generate ideas

- a ranking method to put ideas into priority

- identifying who should take things forward.

Timing

Maximising time is key to structuring your workshop, how many times have you been in a meeting that runs hopelessly over time or leaves little time for certain items. It is very important that however you structure your workshop that you either stick closely to time or build in plenty of contingency.

This could involve timing activities to the minute and using a stopwatch to keep you on track. Remember that everything takes longer than you think and higher participant numbers exacerbate this.

Environment

Think carefully about the space you are using. It sounds obvious but ensure it is large enough and allows people to move around. Also consider what is in the room – for example, do you need tables or flipcharts and if so can these moved?

Advanced information

Do you want your participants to be thinking about anything in particular? If so be sure that you make this clear and are specific about what this is.

- How to network

-

By Charlotte Caroff

Networking is a crucial skill within the professional world, one that everyone can learn yet is rarely taught in formalised environments. As healthcare professionals effective communication is crucial to our success, a valuable transferable skill into the world of networking. Whether you are looking for new job opportunities, seeking advice or looking to expand your network effective networking can provide you with many opportunities that are otherwise not known of.

Here are some of the tips and tricks to help improve your networking skills.

1. Set clear networking goals

Clarify what it is you are hoping to achieve from a networking opportunity – are you looking for advice? Support for a cause or project? Research opportunities? This will provide you with focus to better prepare and frame your approach towards others.

2. Identify your target audience

Who is it you would like to network with - professionals within your industry? Potential mentors? Leaders in their field? This allows you to identify the different environments you should strive to network within.

3. Develop an online presence

Often overlooked within the medical profession, online networks such as LinkedIn can be extremely valuable in facilitating networking opportunities as well as allowing you to maintain professional networks. When updating your information on LinkedIn, the two key sections in your profile are:

- Headlines: add as much key information separated by “|”

- About: you have 2600 characters to describe you, your project and ambitions. Use keywords that people will search within the search bar - it is easier to connect with people if they can find you!

Ensure your profile is up to date, accurate and reflective of you and your goals. Whether it be online or in person, it is important to be yourself. Use these platforms to engage with others, participate in online forums and discussions.

4. Attend in-person networking events

There are various formats within which networking can take place. Attend conferences related to your areas of interest and professional goals, attend workshops and seminars. These in person events provide a valuable opportunity as like-minded individuals will be in attendance. Not all networking opportunities stem from formalised environments, remember opportunities can present themselves at all times!

5. Contribute

Networking is a two-way street, seek out opportunities and connections but be prepared and willing to offer your knowledge and time in return. This will allow you to build stronger relationships with others and will be more valuable to you.

6. Follow up

After meeting someone with whom you have connected with, follow up either via email or other professional route to clarify your intentions and confirm your interest in them and/or projects/opportunities that you have discussed.

Networking is a skill that takes time to develop, not all interactions will lead somewhere. Remember networking can provide you with many opportunities but it is also important to remember the importance of contributing to your networks too.

Happy networking!

- How to reach out to via email someone to purse an opportunity

-

By Charlotte Caroff

There are no limits to what you can achieve if you set your mind to something, but a mentor/supervisor can be extremely beneficial in helping you achieve a goal. Mentors/supervisors can provide you with invaluable guidance and support based on their own experiences and expertise. You may have a project you would like to get up and running or may be interested in contributing to an established project. Reaching out to people and asking for help or offering assistance may be one of the biggest steps in helping you on your way. Below I have set out guidance on how to reach out to someone via email to purse a professional opportunity.

1. Subject line

Be clear in setting out your intention, this should summarise what you are hoping to achieve. For example:

- Request to join project name

- Interest in contributing to project name

- Request for assistance regarding project name

2. Introduction

Briefly introduce yourself and your current position. Outline relevant qualifications, experiences or skills that would make you suitable for this project/your proposed project.

3. Express interest

State why you would like to be involved in the project – be specific if you can. It may be relevant for you to outline your career ambitions or goals if these align with the given project. If you would like to start a new project this is your opportunity to sell your idea, explain why you believe this to be important and what you would like to achieve.

4. Set out contribution parameters

Outline how you would like to contribute to a project/run your project. If you are asking for guidance, be clear on what support you think you may need.

5. Provide opportunity for meeting/discussion

Emails allow you to give the recipient a chance to digest the information, however it may be beneficial to suggest a meeting to further discuss projects.

Do not be disheartened if this approach is not successful, it may take time to find projects/supervisors that are a good fit. Clinical supervisors and education supervisors can be a good place to start and may even be able to sign post you to better fits. Be as prepared in your approach as you can but remember nothing is ever lost by just asking!

- How to use social media to promote communication and engagement

-

By Dr Jonathan Guckian, foundation year 2, Northern Local Education and Training Board

Social media tools have become increasingly popular and diverse, with wide application in the workplace, from managing small businesses to influencing national events [1]. Junior doctors also engage with social media in the context of their training. Practical applications include feeding back on training reform [2] and facilitating research [3].

There is evidence of social media being used for the successful coordination of junior doctor forums, with the mobilisation of large numbers on ‘The Junior Doctors Contract Forum’ on Facebook [4], as well as the establishment of smaller networks where social media is playing a key role within local hospital JDRGs.

This guide aims to provide an overview in how to best utilise social media tools when setting up a JDRG, with the primary aim to improve engagement and productivity.

Do your research

Social media can be a valuable tool when setting up a JDRG, if employed correctly. Successful JDRGs identify what is already being used by staff in a trust and look to adopt those platforms. Asking doctors to migrate to another platform can create an unnecessary barrier to engagement.

TOP TIP: Consider utilising existing social media pages (eg Doctor’s Mess Facebook page) if there is active engagement of trainees already.

Think carefully about what meets your needs as an organisation and if there are any information governance implications – most trusts have a local policy you can refer to and there is also extensive GMC guidance. Key considerations include if there is any risk around the breach of confidentiality or the sharing of inappropriate content [5]. Applications like Whatsapp are effective within small groups, but may not be suitable for an entire junior doctor body at a large tertiary centre.

Choose your social media infrastructure

A JDRG should have a clear communication and social media strategy. Key considerations are how to communicate within a committee, with the junior doctors and with senior hospital leadership. It is usually best to have a dedicated strategy for each and communication methods with management will likely involve some negotiation.

TOP TIP: Instant messaging platforms such as Whatsapp or Slack are usually best for small committees. Facebook and email bulletins can be effective methods to engage with larger groups of junior doctors.

Running a social media account

Maintaining an organisational social media account can require significant effort, rapid response times and constant surveillance of posts. Sharing the workload of writing posts and responding to others can make the role manageable and ensures variation of content.

TOP TIP: Social media when employed in a JDRG context is a portal to the workplace and unprofessional behaviours should be treated as they would at work. Establishing and publicising ground rules can help avoid any problems with confidential information or unprofessional behaviour.

Limitations

Some doctors and students may prefer to use social media platforms on a purely social basis [6], and many will be unwilling to engage due to a lack of familiarity with the chosen interface.

An additional limitation is that online forums can quickly become ‘echo chambers’ which reinforce ideas without appropriate challenge or critical debate. A way to prevent this may be to encourage open and frank debate, challenge peers and ensure that doctors with a variety of opinions are invited to participate.

Further applications of social media

Arguably the most valuable aspect of social media is that it provides measurable information in the form of online polls as well as qualitative data. This can then be taken to management to provide a case for change.

TOP TIP: Some platforms feature ‘trends’ which are tailored to every individual account. This can be used to raise and measure grassroots support.

Suggested further reading

‘Likeable social media’, by Dave Kerpen, explores how to engage people through social media platforms and encourage them to publicise your work.

- How to have effective conversations with seniors and executives

-

By Dr Michael Fitzpatrick, University Hospitals of Oxford

Junior doctor representative groups (JDRGs) provide a platform to effect change through discussion and negotiation with local education leaders and trust executives. Meeting with, and presenting to, senior trust executives can be daunting but often provides the best method to effect real change about important local issues.

Preparation

Define your goal from the meeting or presentation. Align your presentation and planned pitch with your objectives and the allocated meeting time. Spend time crafting your presentation to be as succinct and effective as possible – you may not have much time to make your case so be clear about what the ‘ask’ is.

Know your audience

Identify who is the best person in your organisation to discuss the issue with. It can often be a board member who has direct oversight of the area in question. Take time before the meeting to research their role, background and previous responsibilities. Use this information to try to understand and explore their likely responses. Seek first to understand the other party’s motivations and preferences.

TOP TIP: It can be difficult to make yourself heard by managers and executives who make key decisions. Use your own contacts (eg DME, guardians of safe working hours or clinical leads) to help you access key decision makers.

Approach during the meeting

A presentation to a senior executive is likely to result in several questions about the detail or an area of their interest. These may include points of rebuttal. Try to anticipate any questions and prepare for them. Other people’s priorities and perspectives should inform the tone and angle of your pitch.

TOP TIP: Ask the advice of someone with a management role to help predict what questions might arise and prepare the answers in advance.

Don’t be afraid to argue your point with confidence, but always avoid being rude or dismissive. Prepare in advance to get into the correct frame of mind, then keep to time.

TOP TIP: Try and get a colleague to cover your clinical work and/or bleep, even if only for a few minutes. Clinical commitments can overrun unpredictably and this might be your only opportunity to raise this issue. So give yourself the best chance – you only have one opportunity to make a first impression.

Use the meeting to develop contacts among those you meet. Make sure that as a result of the discussions a firm action is agreed and, if appropriate, written into the minutes.

Following up the meeting

After the meeting, contact those who are responsible for that action to gently push it forward. Email key people to thank them for meeting with you and provide a short summary of your understanding of the points discussed and to confirm next steps.

TOP TIP: If senior individuals have agreed to support an action, it can be useful to copy them into your emails to those individuals responsible for taking actions forward.

If you are discussing issues with trust executives, they are likely to be important and require significant organisational change. Change takes time, particularly within large, complex organisations. Don’t be surprised or disheartened if things take longer than anticipated, and prepare to discuss progress at the next meeting.

Further reading

‘Getting to Yes’, by Roger Fisher and William L. Ury, explores the psychology of negotiations and discusses the method of principled negotiation.