This toolkit is designed to help junior doctors build, sustain and run their own local leadership and engagement structures. Many junior doctor representative groups have been in place for several years, while dozens of new forums have been set up in NHS organisations across the country. The sections below include a number of case studies which showcase good practice from across the country as well as some practical guides to help with the day-to-day management of these groups. We also summarise the relevant academic literature and explain how different local leadership structures relate to existing contractual requirements.

No two organisations are the same, and each will require a tailored solution to help engage and empower their junior doctors. We hope the information in this toolkit will help doctors develop their own local bespoke solutions. The information within the toolkit is not exhaustive and further sections will be added over time. If you have any suggestions for topics which could be included, or want to contribute a case study, please contact us.

The evidence for engagement

This section outlines some of the evidence supporting the value of medical engagement, how forums can help engage junior doctors, and the value they bring to healthcare organisations.

This section outlines some of the evidence supporting the value of medical engagement, how forums can help engage junior doctors, and the value they bring to healthcare organisations.

The content here can be used to supplement business cases for local forums and may also be useful for junior doctors engaging and negotiating with senior executives.

- The value of medical engagement

-

NHS staff are central to the delivery of good quality patient care. Therefore, medical engagement fundamentally alters NHS performance, including patient experience and patient mortality. An engaged workforce is motivated, satisfied, committed, finds meaning to their work, and has advocacy for the organisation. At the other end of the spectrum, poor medical engagement leads to burnout and stress resulting in cynicism, exhaustion, and inefficiency.

In trusts with high medical engagement, employees benefit from increased job satisfaction and well-being, and are more committed to improve outcomes (Organ, 1988). The organisation benefits are numerous, including higher levels of patient safety, improved performance, improved financial management and decreased absenteeism and staff turnover. An organisation with 1 standard deviation higher medical engagement compared to similar providers, typically improves its mortality rate by 2.4%. An average NHS trust with 1 standard deviation improvement in medical engagement will have lower staff turnover and can expect to save over £150 000 in salary costs (West & Dawson, 2012).

These benefits are acknowledged across the healthcare system and are enshrined in the NHS Constitution’s 3rd principle:

“Respect, dignity, compassion and care should be at the core of how patients and staff are treated – not only because that is the right thing to do, but because patient safety, experience and outcomes are all improved when staff are valued, empowered and supported”

Conversely, organisations with poor medical engagement will find it more challenging to improve quality of patient care and organisational outcomes (Keogh, 2013; Francis, 2013; Berwick, 2013).

A number of strategies have been proposed for how to improve medical engagement. These include well-structured appraisals with clear objectives, organising work around well-structured teams with shared objectives, and supportive line management which enables employees to become involved in decisions making.

For junior doctors, 8 high impact actions to improve the working environment currently have system-wide support. Implementation of these actions will improve medical engagement and help trusts achieve the subsequent benefits to operational performance and patient outcomes.

Further reading: what is medical engagement?

Medical engagement is defined as “the active and positive contribution of doctors within their normal working roles to maintaining and enhancing the performance of the organisation which itself recognises this commitment in supporting and encouraging high quality care” (Spurgeon, Barnwell & Mezelan, 2008). Medical engagement is measurable and has a consistent correlation with a number of positive organisational attributes.

Job satisfaction and job commitment are recognised necessary components of medical engagement. However, a third essential factor, working in a collaborative, has also emerged in recent years. Spurgeon suggests that:

“Since team-working and co-operation have always been considered critical to effective patient care it is perhaps no surprise that collaborative working has been found to be the “3rd pillar” in supporting effective medical engagement.”

- The value of junior doctor engagement

-

Throughout their training, junior doctors rotate through numerous departments and trusts. This provides them with a unique exposure to a variety of practices across individual healthcare providers, observing pockets of excellence, as well as incidences where there is room for improvement. Trainees bring a fresh perspective to the traditional clinical practice of institutions and can be flag bearers for innovation and change (Firth-Cozen, 2001). Organisations which employ junior doctors have an opportunity to mobilise agents for change if they can signpost these employees to a productive, influential group which offers development opportunities. (Winthrop, et al., 2013) They are also in a position to identify high performers to retain outside of formal training structures through dedicated leadership or quality improvement positions.

Junior doctor engagement in quality improvement (QI) and patient safety (PS) endeavours results in a healthier transparent learning culture, reduced medical errors, and improved organisational performance. When employee time and organisational resources are correctly assigned value, QI/PS work demonstrates a significant return on investment for healthcare organisations (Roueche & Hewitt, 2012). Individual QI initiatives led by junior doctors have resulted in organisational savings of over £300 000 due to improved use of resources and more effective deployment of staff (Palmer et al, 2013). Meaningful junior doctor engagement also results in significant reductions in clinical errors as well as improvements to patient care outcomes (Prins et al, 2010).

Conversely, without dedicated engagement initiatives, junior doctors often selectively disclose errors informally (Kroll, et al., 2008) and clinical error reporting becomes primarily nurse-driven (Evans, et al., 2006) exacerbating inter-professional silos. At an organisational level, the invariable result of poor junior doctor engagement is disengaged, disenchanted cynical senior clinicians (Wathes & Spurgeon, 2016). A King’s Fund report on medical engagement recently stated:

“medical engagement should not be an optional extra, but rather an integral element of the culture of any health organisation and system.” - Clark & Nath (2014)

Employees identify strongly with an organisation they feel empowers them to deliver positive change. They will derive greater professional satisfaction after understanding and improving the systems they work in. These aspects are the basis of high-performance work systems and have a strong positive correlation with increased performance outcomes (Messersmith, et al., 2011).

- Junior doctor forums to improve junior doctor engagement

The best predictors of junior doctor engagement are being valued, acknowledged, heard and involved (Spurgeon, Clark, Ham, 2011). A recent HEE publication [REF: Health Education England (2017) – junior doctor morale: understanding best practice working environments] has focused on implementing changes to tackle disengagement on junior doctors.

There are multiple barriers to effective engagement of junior doctors. This is both from an organisational perspective, including issues such as:

- frequent rotation and turnover of staff

- variety of required approaches for different grades and specialties of junior doctor

- poor connections between front-line staff and senior leadership

as well as from the junior doctor perspective, including:

- poor work-life balance

- mismatch between training and service delivery experiences

- time required to settle in a new post and gain tacit knowledge of the organisation

- fears over possible negative ramifications on career progression of reporting themselves or senior colleagues

Wathes & Spurgeon (2016) suggest that forums for junior doctors could address a number of these barriers and thus improve medical engagement. Their work makes reference to informal, organic groups in keeping with communities of practice (CoP) – often defined as a group of people who share a concern or passion and learn how to do it better as they interact regularly. Forums of this nature already exist as vehicles of employee-driven innovation in corporate settings.

This toolkit is designed to help junior doctors build, design and run their own representative structures. The next section will describe the potential structure of these groups and showcase some that have already been set up at various trusts.

N.B. Since 2016, the Junior Doctor Terms and Condition of Service (TCS) has placed a non-negotiable requirement on all NHS employers in England to establish Junior Doctor Forums (JDFs). These are contractually focussed and act as a tool to protect training and safeguard working conditions as well as the well-being of junior doctors at trusts. We distinguish these two distinct bodies within this toolkit. Contractually focussed bodies are referred to as JDFs, whilst organic groups based around a CoP are described as Junior Doctor Representative Groups (JDRGs). We outline the differences between these bodies in a later section of this toolkit.

Forming a representative group

Since the implementation of the 2016 junior doctors terms and conditions of service (TCS) in England, junior doctors’ forums (JDFs) have become a contractual requirement for hundreds of trusts across the UK.

JDFs can only include doctors employed at the trust and have a narrow focus around contractual obligations. JDRG membership can include doctors from other organisations and often have a broader agenda. JDFs and JDRGs can be separate, distinct bodies, or a JDRG can incorporate the functions required of a JDF. The case studies in this toolkit outline different models for accommodating both structures.

- Junior doctors’ forums (JDFs)

-

The 2016 junior doctors terms and conditions of service (TCS) include a non-negotiable requirement for each NHS trust in England to appoint a guardian of safe working hours (GSWH). The guardian, in partnership with the director of medical education (DME), is required to establish a JDF to advise them. The JDF reports to the Board, the postgraduate training committee, medical staff committee, and LNC (local negotiating committee) at their quarterly meetings.

Responsibilities of this forum include:

- the discussion of contractual issues raised by employed junior doctors

- the review of exception reports, work schedules and rota compliance

- the review, discussion, approval and distribution of income raised through fines levied as a result of exception reports

- involvement in the performance management of the guardian to ensure this role is undertaken to a high standard.

JDF core members must include the local negotiating committee (LNC) Chair and relevant LNC junior doctor representatives. They should be accompanied by doctors elected from the employed trainees. Employers are required to make necessary arrangements to facilitate these forums, including allowing elected representatives to arrange time off for their JDF activities and duties, and integrating forum meetings into their work schedules.

JDFs can also benefit from the attendance of other individuals (or their deputies) including:

- directors of medical education

- HR directors

- Trust rota co-ordinators

- Trust executive directors

Attendance of other members should be negotiated at a trust level. This usually includes representatives from each sub group of the junior doctor population, elected on an annual basis.

In addition to overseeing contractual responsibilities, the Keogh Report (2013) outlined that JDFs will “provide a forum for the trust to engage with and harness the energy and vision of junior doctors in developing and improving services, working conditions, education and training.”

Many NHS trusts already have a network or meeting of junior doctor representatives. Some have similar roles to JDFs but are less formal, with a junior doctor as chair and with only the DME in attendance on behalf of the trust. Others are more closely related to a junior doctor representative group and community of practice model.

New JDFs were not necessarily intended to replace existing forums, particularly if the existing structure can fulfil the remit and responsibilities of a JDF. Similarly, if an existing forum has traditionally had a different focus, there is no imperative to replace or merge it, and the two forums can co-exist. There are two case studies described in this which toolkit demonstrate this point. Both Nottingham University Hospital (NUH) and Oxford University Hospitals (OUH) have JDRGs with distributed leadership structures - NUH has chosen to integrate the requirements of new JDFs, while OUH has opted to have two co-existing forums.

Prior to the implementation of the 2016 TCS, most forums for junior doctors had a similar format to JDFs, but without formal recognition in NHS trust targets and without the role of the guardian. The introduction of the contract has seen JDFs become compulsory and has introduced the guardian.

- Junior doctor representative groups (JDRGs) and communities of practice (CoPs)

-

Junior doctor representative groups (JDRGs) are a more dynamic way for junior doctors to engage with their employing organisation and contribute to its wider organisational priorities. JDRGs are not defined by contractual requirements or other guidance, and their membership is not limited to doctors who currently work at the host trust.

Many JDRGs have existed for a number of years prior to the implementation of the 2016 TCS, some have been created more recently. There is no national, formal review of their structure and function, but anecdotal evidence suggests that most have been launched by or with the support of the DME.Early JDRG models were similar to informal JDFs. Junior doctors would discuss training concerns as a homogenous group and these would be addressed by the DME and postgraduate centre manager. More recently these forums have evolved due to emergent leadership from junior doctors and a need to address training concerns raised by LETBs (Local Education Training Boards) or Deaneries, the GMC, or trainee surveys.

JDRGs, especially those launched or re-designed by junior doctors’ leaders, are in keeping with communities of practice (CoPs). A CoP has three components that distinguish it from other forums or networks – a domain, a community, and a practice:

- Domain – a clearly defined shared interest and a commitment to that end (eg improving junior doctor training, improving patient safety etc)

- Community – members of a specific domain interact, collaborate, and share information with each other. Community co-ordinators (or representatives) are key to maintaining the group dynamic

- Practice – members share resources which can include stories, tools, experiences and solutions. Problems are shared and solved together in the social learning environment. Community co-ordinators and community librarians are responsible for making sure these conversations are ‘cutting edge issues’ for expert members. More junior members are often inspired by expert problem solving and gaps between member knowledge can be bridged by mentoring or buddying to keep the CoP together.

This model has been replicated in NHS settings (see Case Study: Oxford University Hospitals JDRG and Case Study: Leeds Teaching Hospital Trust JDB). JDRGs can still get senior management and executive buy-in if they are linked to organisational outcomes such as patient safety (Case Study: Hull) and morale and leadership (Case Study: Nottingham University Hospital). JDRGs that evolve from the top of organisational hierarchies produce more sustainable change and improvement in outcomes (Wathes & Spurgeon, 2016).

JDRGs are an excellent vehicle for organisations to improve engagement with junior doctors and empower them to contribute to the organisation’s objectives. JDRGs in a variety of structures across the country have contributed significantly in domains of quality improvement, leadership training and workforce engagement. Their role can encompass much of the contractual responsibility required of JDFs and provide additional value to trainees as well as their organisation. JDRGs can also provide junior doctors who no longer work at the trust a way of continuing to contribute to ongoing improvement work.

Suggested further reading

CoPs are a concept evolved from a learning theory on the idea of legitimate peripheral participation (Lave & Wenger, 1991). CoPs are “groups of people who share a concern, a set of problems, or a passion about a topic, and who deepen their knowledge and expertise in this area by interacting on an ongoing basis” (Wenger et al, 2002).

CoPs are organic and distinct from a hierarchical line management structure. They can exist within large organisations in order to yield innovation over time. In corporate settings, employers have hired knowledge managers and provided resources for employees to create a CoP, eg Google (Bates, 2017) and Shell (Wenger et al, 2002).

Leading within your organisation

This section offers practical advice for leading as a junior doctor, including running and managing a junior doctor representative group (JDRG) to develop valuable skills for which directors of medical education (DMEs) could consider providing local training.

Topics discussed include how to successfully chair a meeting, how best to negotiate with seniors and executives, and how to use social media for the benefit of you and your colleagues.

- How to engage patients and the public

- How to Chair a meeting

- How to have effective conversations with seniors and executives

- How to use social media to promote communication and engagement

Case studies

This section contains a number of case studies that outline different JDRG structures. Many are focused on junior doctors in training with some incorporating trust grades in their membership as well. These case studies showcase different models of working as well as different topics of focus.

Distributed leadership

Distributed leadership

Distributed leadership focuses on networking and collaboration between individuals with formal leadership positions and those who do not.

Unlike hierarchical models of leadership, this a flexible approach which allows an individual to have both a leader and follower role within an organisation, depending on the situation.

Junior doctors are a varied, non-homogenous group who can benefit from distributed leadership structures to improve medical engagement and organisational change.

- Oxford University Hospitals (OUH) NHS Foundation Trust

-

By Dr Michael Fitzpatrick, specialist registrar gastroenterology, University Hospitals of Oxford, 31 July 2018

The director of medical education (DME) at Oxford University NHS Foundation Trust developed a range of forums for junior doctor engagement with the trust, via representative groups, which meet, individually, with senior executives 10-12 times a year. These forums include a foundation year group, core medical trainee group, medical registrar group and more recently a surgical and anaesthetic group. The medical education department provides administrative support as well as refreshments or a meal at meetings.

Each group is chaired by a junior doctor, who sets the agenda and is responsible for organising the meetings. This structure emphasises that the forum’s agenda is focused on the needs and concerns of trainees, and encourages attendance and discussion.

Senior executive presence at meetings enables effective decision-making and action planning within the meeting itself. In Oxford, at the DME’s invitation, the Medical Director and the Chief Executive have attended several of these groups. This has enabled trainees to raise matters of concern at a high executive level.

The groups are now the established platform for trainee engagement and junior doctors are able to effect change within medical education and training, non-contractual issues and in quality improvement endeavours. The biggest challenges have been to maintain the momentum of the groups and ensure regular attendance, especially as trainees rotate frequently and have heavy on-call commitments. To address this, the chairperson and DME identify and recruit trainees and promote the forum and its work amongst their colleagues.

Recent achievements arising from the Oxford medical registrar forum

Medical education and training

- New, trainee-led, case-based discussion teaching session

- Live-streaming and recording educational sessions

- Directory of educational meetings within trust

- Survey of teaching provision between higher medical specialties

- Launch of CMT careers fair (in conjunction with CMT forum)

Quality improvement

- Directory of clinical/ambulatory services

- Junior doctor consultation on trust initiatives (eg 24/7 care toolkit)

- Improvement initiative of ECG facilities on wards

Junior doctor morale and engagement

- Survey of non-contractual issues for junior doctors

- Presentation on morale and non-contractual issues to medical director and executives

- Nottingham University Hospital NHS Trust

-

By Dr Sarah Barlow, foundation year 2, Nottingham University Hospital, 31 July 2018

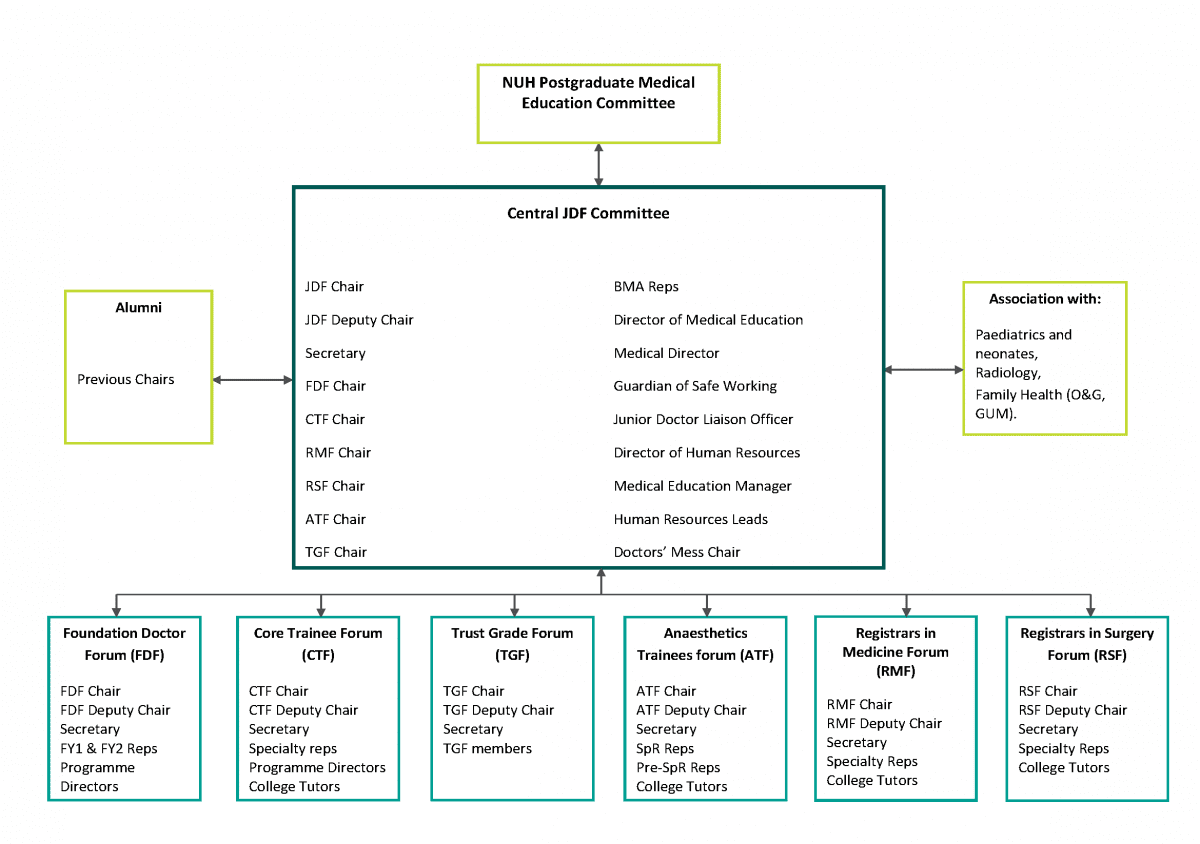

Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust (NUH) is a large teaching hospital with approximately 900 trainees. Its JDRG that was redesigned in 2015 using a distributive leadership framework. This resulted in a network of sub-forums reporting to a central committee, which included representation from senior trust management including the Medical Director, Director of HR and DMEs. This structure is illustrated in the below image.

In advance of meetings, the central committee receives minutes from each sub-forum and representatives present issues that require escalation. This enables timely, proactive resolution of issues. Links exist with existing forums in radiology, paediatrics and family health (O+G and GUM) and these committees have not been restructured.

Cross-site video links have enabled individuals to attend meetings at their own site, resulting in a consistent improvement in attendance. In parallel, committee members have adopted social media, email and newsletters to aid communication and transparency. Recruitment now takes place in advance of August changeover, with the HR team sending out requests for expressions of interest to incoming trainees.

In response to the 2016 junior doctor contract and the requirement of every trust to have a junior doctor forum (JDF)to discuss contractual issues such as exception reporting, Nottingham integrated the functions of a JDF into its central JDRG committee. The central JDF meeting now includes representation from the guardians of safe working hours (GSWH) and the Local Negotiating Committee (LNC). The meetings are chaired by the GSWH on a quarterly basis.

Recent achievements arising from the Nottingham JDRG

Medical education and training

- Addition of a trust grade doctor forum to facilitate SAS doctors’ development needs

- JDRG is now embedded into the trust’s educational governance structure

Quality improvement

- Currently being integrated into trust’s patient safety and quality improvement governance structure.

Junior doctor morale and engagement

- Appointment of a junior doctors’ liaison officer

- Comprehensive email database of all doctors in training

- Q&A sessions with senior management to discuss concerns around the introduction of the 2016 junior doctor contract

“The new structure of the JDRG helps the trust hear issues and concerns from all the different groups of trainees working at our hospital. It is great to hear these first-hand and to be able to offer support and occasionally provide help to remove blockages to the trainees getting the help they need. The JDRG provides a great opportunity for trainees to develop different leadership skills and we recognise this by providing evidence for their GMC portfolio. The forum has developed very positively in the last year or so and I look forward to continuing to work with them to make NUH a great place for trainees to come.” - Nicky Hill, Director of Human Resources

Running a JDRG with a particular focus

JDRGs can focus on specific themes that are strongly aligned with key organisational objectives. Quality improvement and patient safety as well as leadership development are of importance to NHS Trusts.

JDRGs can improve the quality and safety of patient care and provide training for the benefit of trainees, the organisation, and patients, and there is extensive evidence that ventures which place junior doctors and senior management together in the pursuit of quality and safety have favourable outcomes (Howlett, et al., 2011) (Lemer & Moss, 2013).

- Quality improvement and patient safety: Junior Doctors Together (JDT), Hull and East Yorkshire Hospitals NHS Trust

-

By Dr Alan Gopal, academic core trainee anaesthetics, Hull and East Yorkshire Hospitals NHS Trust; Dr Anna Greenwood, founding chair of Junior Doctors Together; Dr Elizabeth Hutchinson, vice-chair of Junior Doctors Together – 4 September 2018

JDT is one of three JDRGs across Yorkshire. JDT is based in Hull and East Yorkshire Hospitals NHS Trust, which encompasses two tertiary teaching Hospitals. It is an internal JDRG which provides a platform to support work and discussion around quality improvement, patient safety, and junior doctor engagement outside of training programme and contract-related matters. Its functions were agreed between the medical education department, senior management and junior doctor representatives and include:

- Junior doctor representation

- An innovation platform

- A forum to retain institutional memory.

This case study gives emphasis to the important role junior doctors can play in improving the quality of care, and how this can be nurtured in collaboration with NHS Trusts through their JDRG. A unique feature of this JDRG is an emphasis on organisation memory and talent management throughout the group. Juniors often maintain involvement with the group despite rotation to other hospitals in the region. This long-term engagement fosters organisational change and encourages the junior doctors to build up areas of interest and expertise as they continue to work with senior staff over time, learning non-clinical skills and building up a tacit understanding of the organisation also.

The JDT has a distributed leadership structure. Two junior doctors hold the chair and vice-chair positions of the group to manage the group’s administration and chair the monthly meetings whilst members take responsibility for their various projects. The Trust’s chief executive officer, director of medical education and deputy chief medical officer or their deputies attend each meeting; facilitating and supporting the learning of the junior doctors and the organisation itself by providing advice and opportunities in an approachable environment.

Successful quality improvement projects include:

- reducing food wastage by exploring the possibility of providing unwanted patient food to staff

- improving inpatient phlebotomy services to the benefit of patient flow and junior doctor training

- improving the facilities available for those caring for dementia patients (i.e. family or friends) to stay overnight with their loved ones.

A current ongoing project is examining how to enhance widening participation across the locality in partnership with the Hull York Medical School.

Recent achievements arising from Junior Doctors Together:

Medical education and training

- Reducing junior doctor workload

- Providing supported leadership and management learning experiences through access to opportunities and senior management in an environment with a shallow authority gradient.

Quality improvement

- Improvements to phlebotomy service to accelerate patient discharge and reduce junior doctor workload

- Reducing inpatient food wastage and increasing ward staff morale

- Improving overnight facilities for dementia carers

- Enhancing local widening participation.

Junior doctor morale and engagement

- Long-term engagement of both junior doctors and senior management noted.

- Leadership: Junior Doctor Body (JDB) - Leeds Teaching Hospital Trust (LTHT)

-

By Mr Stuart Haines, General Manager for Medical Education; Dr Rammina Yassaie, Clinical Leadership Fellow and ST3 paediatric trainee, Leeds Teaching Hospital NHS Trust – 4 September 2018

LTHT established Trust-Level Clinical Leadership Fellowship (CLF) posts as part of Yorkshire and Humber’s Future Leaders Programme. These are 12-month OOPEs for junior doctors, appointed by competitive interview. This scheme is now in its fourth year with 6 CLF’s currently in post, including a pharmacist and radiographer.

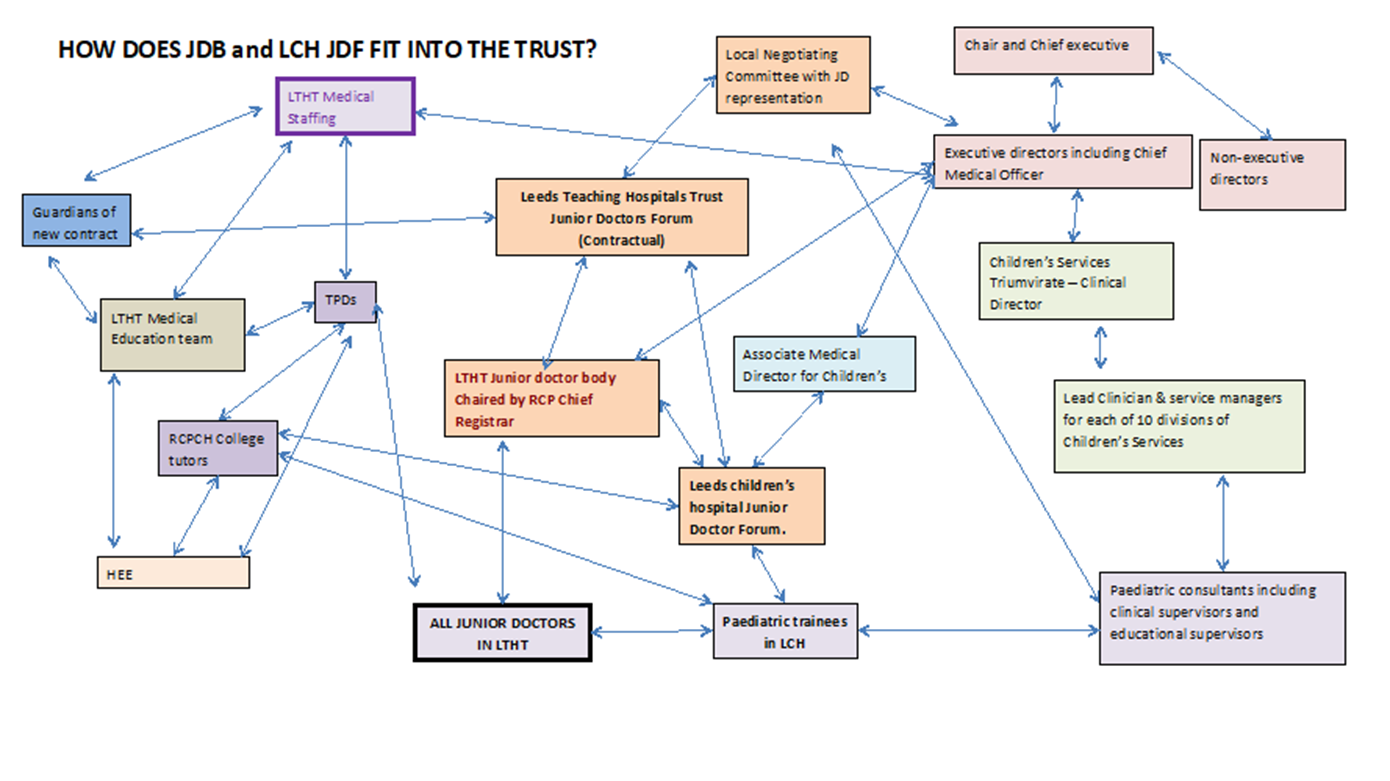

The 2015-2016 cohort of CLFs established the JDRG, known as the Junior Doctor Body (JDB), to increase opportunities for junior doctors to gain leadership and QI experience. The JDB has junior doctor representatives from all specialties and grades and is chaired by LTHT’s appointed Chief Medical Registrar (recruited through RCP’s Chief Registrar initiative). The JDB meets monthly and the Trust’s Chief Medical Officer (CMO), Associate Medical Director or General Manager for medical education are routinely in attendance, along with 15 - 20 junior doctor representatives.

Through this body, junior doctors are represented on Trust-wide working groups and committees including the ‘Lessons learnt’ Group, Clinical Guidelines Group and Quality Improvement Group, where their unique insight and ideas are valued. The interactions between the JDB, the Leeds Children’s Hospital Junior Doctor Forum, the LTHT contractual JDF and other bodies within and outside the trust are outlined in the diagram below.

- Leadership: Junior Doctor Forum - Leeds Children’s Hospital (LCH)

-

By Mr Stuart Haines, General Manager for Medical Education; Dr Rammina Yassaie, Clinical Leadership Fellow and ST3 paediatric trainee, Leeds Teaching Hospital NHS Trust – 4 September 2018

One Junior Doctor Body (JDB) branch is the Leeds Children’s Hospital Junior Doctor Forum (LCH JDF), which was created in response to poor attrition rates and GMC survey results in paediatrics. Approximately 100 junior doctors work at Leeds Children’s Hospital and all are invited to partake in the forum at the start of each rotation. The LCH JDF has a steering committee of 15 – 20 trainees across all training grades and paediatric sub-specialties that meet monthly. However, trainees who wish to attend on an ad hoc basis are also welcomed.

LTHT’s Chief Executive and Paediatric Clinical Directors supported the initiative and it’s success in improving trainee engagement, morale and leadership experience has led to the development of a Chief Paediatric Registrar post, which will be piloted in August 2018, mirroring the RCP Chief Medical Registrar post.

LCH JDF consists of 4 working groups with 3 – 12 trainees in each, with each working group having its own 'lead trainee':

- Morale & Retention

- Teaching & Training

- Workforce Planning

- MRCPCH Examinations

College tutors attend the LCH JDF meetings every alternate month, and the key outputs of each LCH JDF meeting are discussed regularly with Children’s Hospital General Manager and Associate Director to maintain good relations between trainees and the senior managers.

Recent achievements arising from the JDB and LCH JDF:

Medical education and training

- Funded Myers Briggs training sessions for all JDB members to aid leadership development

- Dedicated MRCPCH revision course with 100% of participating trainees stating that they felt more valued by the trust as a result

- Established pre-defined learning plans resulting in improved clinic attendance and e-portfolio engagement

- Junior Doctor App with clinical guidelines and Trust policies

- Monthly Junior Doctor educational newsletter - “Doctor’s Digest”.

Quality improvement

- In-house QI training sessions for staff

- Numerous projects improving patient flow and waste reduction.

Junior doctor morale and engagement

- Dedicated “Improving Junior Doctors Working Lives” working group attended by Post-graduate Directors of Medical Education, General Medical Education Manager, Professional Support Manager as well as junior doctor representation (the chair of the JDB and LCH JDF are frequently in attendance)

- “Walk in my shoes” initiative encouraging junior doctors to shadow senior medical managers in order to gain better insight into their roles

- LTHT “Junior Doctors Awards” presented to Junior Doctors by the CMO and Chief Executive

- In-house Mentoring Scheme for Paediatric Trainees (M-PATHY)

- Trainee representation on College Tutor interview panels to provide trainees with ownership of their training

- Development of new Trust policies to improve work-life balance and flexibility for junior doctors

- Improved Doctors’ Mess Facilities including a specific Children’s Hospital Doctors Mess.

- Communication and engagement: Junior Doctor Representative Group - Tameside and Glossop Integrated Care NHS Foundation Trust

-

Dr Beth Hammersley, Director of Medical Education, Tameside Hospital; Ms Pam Robinson, Postgraduate and Undergraduate Medical Education Manager – 4 September 2018

In 2013 the trust was placed into special measures and under enhanced educational monitoring following concerns over unsafe patient safety and training environments. To address some of these concerns the Board and DME initiated meaningful engagement with junior doctors through a JDRG focused on long-term outcomes. This was paired with direct communication lines between the business unit and postgraduate medical education department. These reforms have coincided with improvements in the trust’s CQC rating and in various domains on the GMC survey.

The main challenge was to rebuild the trust’s reputation around patient safety and training. Many trainees were genuinely worried about working at Tameside and potential risks to careers – this was overcome by empowering them and creating infrastructure to value their voice. This had to be done in a constrained financial environment and a success of the business model was to recognise the collective long-term payback from short-term costs of small interventions (e.g. DME’s time for educational activities was increased from national standard of 1 day a week to 2 day a week in recognition of the scale of the responsibility).

The JDRG was initially poorly attended. Following trainee input, it was moved to the doctors’ mess to give junior doctors ownership of proceeding and held at lunch time to facilitate attendance. Trainees determined the attendee list, which included:

- Medical director

- Head of HR

- Royal College tutors

- Patient safety officer

- Business managers

These changes resulted in a greater than threefold increase in attendance. This forum takes place every month and have achieved a number of significant improvements to training and service delivery. Each division has its own sub-forum to enable trainees to discuss specialty specific issues in depth.Higher level trainees were still not attending the JDRG and it was subsequently discovered that they have distinct issues and often tend to work in greater isolation from other junior doctors. As a result, the ‘Yellow Forum’ (named after their lanyards) subcommittee was setup with the Medical Director and DME. At its opening, 50% of eligible trainees attended this forum, which takes places every 4 months.

Recent achievements arising from the Tameside JDRG:

Medical education and training

- Educator development programme in quarterly in-house development days for supervisors, funded external trainer to revalidate consultants, dedicated educator appraisals

- Trust strategy to value educators through appropriate remuneration, additional input into the ARCP process and a two-way information channel

- Improved ARCP and exam outcomes as well as undergraduate feedback

- Consultant post applicants now specifically seek out medical education department education to demonstrate their commitment to training to the Trust.

Quality improvement

- Appointing a designated patient safety for junior doctors who reads all trainee submitted forms and directly feeds back action points to submitter

- 24 hour monitored anonymous email inbox for raising concerns.

Junior doctor morale and engagement

- Monthly training surveys and DME hospital rounds

- Instant communication to all foundation trainees

- Extensive feedback infrastructure to monitor improvement journeys in partnership with trainees

- Leadership and management opportunities including QI projects and shadowing senior leadership.

- Junior doctor forum: Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital

-

Dr James Rowson, foundation year 2, Norfolk and Norwich Hospital – 4 September 2018

The 2016 junior doctor Terms and Conditions of Service (TCS) requires each Guardian of Safe Working Hours (GSWH) and Director of Medical Education (DME) to establish a Junior Doctors Forum (or for a) to advise them. Many trusts which did not previously host a JDRG have opted to have a standalone JDF as part of this contractual responsibility.

Junior Doctor Forum – Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital

The Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital (NNUH) JDF was started by the hospital’s BMA Junior Doctor representative in collaboration with FY2 and GPST colleagues. Its remit was as outlined in the 2016 TCS:

- Working conditions

- Education and training

- Supporting and scrutinising the guardian

- Distributing fines from exception reports.

It was created before the 2016 TCS came into effect, in order to be running when the GSWH was appointed and before any junior doctor transitioned to the new terms. The JDF is chaired by junior doctors, currently the local BMA representative, with executive sponsorship of the GSWH and DME. It has a constitution agreed by its members and ratified by the Local Negotiating Committee (LNC). Junior doctor members of the forum are responsible for minute taking and secretarial duties.

In addition to the formal reporting and advisory model stipulated in the 2016 TCS, the NNUH JDF acts as an informal mentor/mentee and staff-side/doctor communication channel. To accommodate this two-tiered system, its constitution describes a “JDF Proper” and a JDF “Support Forum”.

The JDF Proper requires a quorum, including the following members (or their deputies):

- GSWH

- DME

- JD LNC Rep

- Workforce Director

- Medical Staffing Director

- BMA Industrial Relations Officer.

Representatives of grades or specialties also attend meetings.

The Support Forum is attended by specialty or grade-representatives and staff from the quorum, and supervisors, are invited (but not mandated) to attend.

Communication and engagement challenges

Originally, all meetings of the NNUH JDF were planned for 17:30, however despite significant communication campaigns, reps on the ground and the use of social media, attendance at these hours was poor. Non-attenders cited three main reasons:

- still being at work at the end of a shift

- having finished a shift too early to justify waiting for the JDF to start

- lack of remuneration for attending the forum despite being work-related.

50% of JDF meetings are now scheduled to be within working hours. Initial feedback on this change and the proposal to provide catering is positive. Advertising meeting dates several weeks in advance with a reminder 24-48 hours before the meeting appears to be the most effective way to ensure junior doctor attendance. A core group of representatives disseminating information by word of mouth has also proven effective. Senior staff attendance normally requires six weeks notice.

Stage of training specific forums

By Dr Marc Davison, Director of Medical Education, Buckinghamshire NHS Foundation Trust; Dr Tasmin McAllister; Dr Amir Khaki – 17 July 2018

Many issues arising at the start (foundation year) and end of training (specialist registrar) are significantly different and this disparity often warrants dedicated sub-forums for stages of training, as well as for individual specialties. The success of distributive leadership models relies on the strength of individual sub forums.

Registrar forum

The Oxford University Hospital (OUH) case study in the section above includes a description of a specialty registrar forum as well as its outcomes. These forums often have a strong focus on leadership development, targeted for senior trainees.

Creation of specialist registrar forums can be a powerful resource to improve levels of medical engagement of the whole junior doctor cohort. Many registrar forums are heavily involved in consultation on new trust initiatives and often devise development schemes to support junior colleague (eg CMT careers fairs).

The Tameside Hospital case study highlights how specialist registrars can be isolated and not engage with a trust-wide JDRG. Tameside’s bi-monthly ‘yellow forum’, resulted in several QI projects as well as the development of a senior leadership shadowing programme. This was of benefit to both junior doctors and senior management.

Foundation forum

Finishing medical school and starting a foundation training post is one of the biggest transitions in a doctor’s medical career. Foundation year forums or JDRGs could be a place where a trust could tap into new ideas from multiple regions, continue leadership development and increase rates of socialisation and the understanding of the NHS, and the organisation culture.

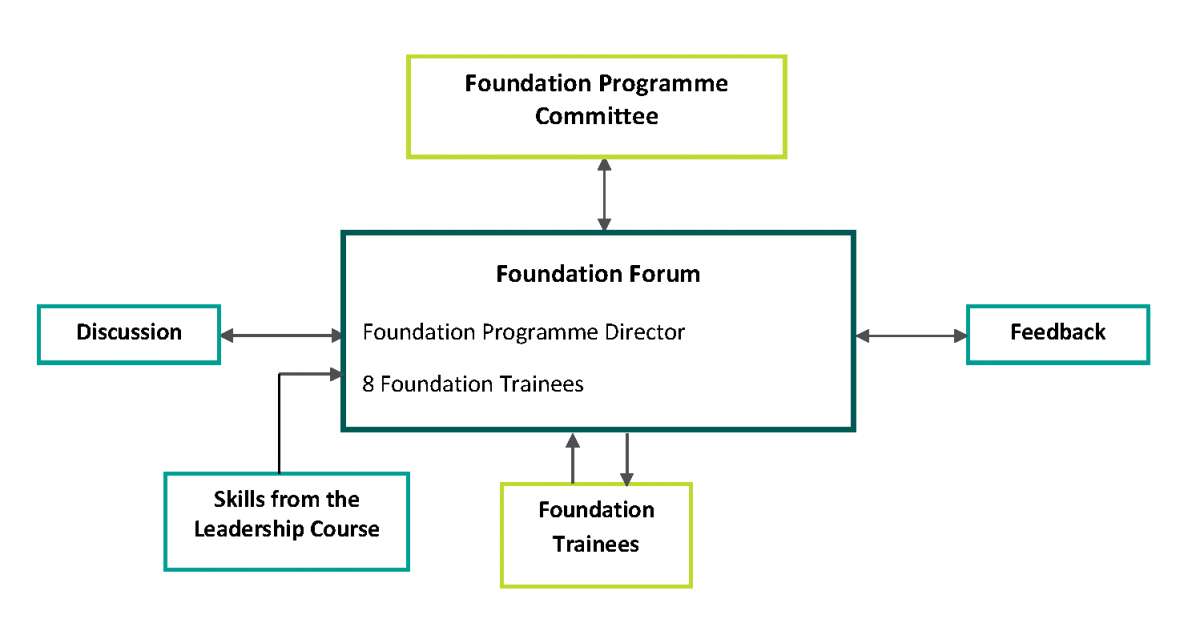

Buckinghamshire NHS Trust Foundation Forum

This forum was initiated by the trust’s foundation programme director (and now current DME). It was created due to increasing numbers of foundation year junior doctors, poor feedback on GMC surveys and lack of resolution to ongoing training and service issues. The forum consists of eight foundation year junior representatives and is chaired by the associate director of the foundation programme to provide organisational memory. Meetings take place four times a year, with a formal agenda and minutes, and are paired with informal interim meetings to discuss progress on action points.

The eight representatives were given study leave to attend a funded leadership course, specifically designed for foundation year doctors. This consisted of eight half day sessions which included guest speakers and interactive workshops on topics such as communication skills, NHS structure, and using basic leadership skills to enhance effectiveness.

Recent achievements arising from the Buckinghamshire Foundation Forum

Medical education and training

- Improved educational opportunities and clinical support for foundation doctors working in Trauma & Orthopaedics.

Quality improvement

- Audit and research presentation evening with peer-reviewed prizes and a regional competition.

Junior doctor morale and engagement

- Development of feedback pathways from forum members to foundation programme committee, and from forum members to trainees

- Trainee feedback survey focusing on clinical supervision process.